Santie Veenstra

Santie Veenstra is one of the colourful protagonists in our trilogy. She has a dreadful childhood.

This is chapter 10 from A Family Affair, a trilogy by Bernard Preston.

- Bernard Preston homepage

- A Family Affair

- Santie Veenstra

Most children lead colourless childhoods, nothing out of the ordinary, even drab and grey, with little to write upon or comment; just ordinary.

It’s nice to have an ordinary childhood. Santie Veenstra would have given much more than her eye teeth to have enjoyed the privilege of a colourless childhood. But some, poor dears, her aunt Maggie once said to her, are less blessed, fate having predestined them to lead exciting and tempestuous lives. Little of the gentle, ordinary passage of time seems to pass and the great gulfs that lie between the mountaintops are the deeps are pitted with snares and swamps.

Oliver Twist had such a life. Great literature, but who would want to be an Oliver? Interesting, challenging, character making; and mostly very painful. Man was born to suffer and very often his children too, Aunt Maggie said to her husband Bob, once she discovered what was happening. Over a million children die every year in Africa of the consequences of starvation, but Santie Veenstra didn’t die. She only wished that she had.

A Family Affair

Santie Veenstra

Santie was born into an ordinary family in the small South African town of Boksburg. South Africa is also a melting pot, and having an Afrikaans father, and a mother born in Europe was not so unusual. Her father, Klok Veenstra, was a cabinetmaker of some fame, though he was a solitary and silent man with few friends latterly, not remotely like the tear-away, bawdy rugby player of his youth. Throughout her childhood Santie could remember the sounds of saws, pleasant when they were sharp but high pitched and terrifying to the ear when the ripping teeth were blunt. Father could not afford to have them sharpened every week so he spent half an hour each day sharpening them himself.

It was the thicknesser that Santie really hated. Father always wore earmuffs and Santie would not venture near when he was doing the final preparation of his raw timber. Her favourite was the lathe, and she loved to watch him as her father cut deeply into the shapeless timber with his chisels and shapers.

She could see from the expression on his face how her father loved to cut deeply, to shape and mould but he didn’t have the time or the patience to sand the finished lamps and stands, or the clocks. That was Mommy’s job. She even allowed Santie to help with some of the sandpapering, but she was always attentive. Carpentry machinery is unforgiving, she said over and again to Santie.

Santie adored her daddy. She often walked with one little finger in his hand to Kindergarten or the shops. The same father who loved to cut deeply into the wood he so loved.

Mommy was more forceful and often angry but it wasn't for many for years until Santie realised that it’s only the very lucky child who doesn’t have at least one irritable parent. A very talented woman, love had propelled Francesca into an early marriage and a pregnancy that was not entirely welcome. Good Catholics don’t have many options, she said. Still, she loved her daughter and was determined that she would have the opportunities that life had denied her mother.

Klok’s sister, Aunt Maggie, who lived around the corner, often said that the child was born with a racquet in her hand. By three Santie was batting tabletennis balls around the floor of the garage with Mommy, long before she could reach the table. By four it was a shuttlecock that was being smashed about with an old squash racquet with a shortened handle.

Finally, aged six, Santie was ready for her mother’s passion; tennis was the name of the game. Every afternoon after school it was the same. The same place, the neighbour’s court, the same words: ‘Nothing less that the professional circuit for you my girl, you’re going to be famous.’ Mommy was both right and wrong, Santie realised years later. Famous, yes, but not at tennis. She did turn out eventually, ten years after the pain began, to be a reasonable tennis player, but she never reached the heights that her Mommy dreamed of.

Aunt Maggie, though she had no children of her own, used to say it is wonderful to dream and plan our children’s futures, but it’s mostly to no avail. Circumstances intervene, or the rotten kids want to build their own dreams. Aunt Maggie said we shouldn’t be dreaming our kid’s dreams anyway. Santie didn’t really have many dreams. She was just an ordinary little girl in a very ordinary Boksburg family. Dreams, when they finally did come, weren’t the kind she wished for.

The fateful day dawned, the first deep, when Santie was only twelve. Now there is a glimmer of hope for the writer. Ah, now maybe something noteworthy, something out of the ordinary! Santie’s father asked her to take her mother a cup of tea in bed: ‘You look sick, Mommy. Are you all right?’ Santie had already noticed that the sandwiches that were ready for her every morning had not been made.

‘Yes, I’ll be fine darling. Just a bit of a headache and a stiff neck. Daddy will take you to school this morning. You have got a clean skirt for the tournament this afternoon, haven’t you?’ She looked over her daughter approvingly. ‘Here, give me a love and I’ll see you this afternoon. If I’m a bit better I’ll come to the match.’

Santie won the match but it was her last game of tennis for nearly five years. Tennis didn’t seem to please after that. Santie never saw her mother again after that fateful morning. Not alive, that is. Somebody had told Father that Santie must look into the coffin, so that she would know that Mommy was really dead. She was really dead all right. Just a bit of a headache and a stiff neck, with a high temperature as it so happens, but then Santie didn’t really know much about temperatures. Nor did her mother, and it turned out to be a rather unfriendly little bug, her father started saying. By the time Mommy got to the doctor it was too late. ‘Meningitis does that, Santie,’ Aunt Maggie said, hugging her niece tightly. ‘I’m so sorry.’

The words stuck with Santie for the rest of her life: Unfriendly little bug. Bugs terrified her after that. She was forever swatting and squashing them.

Santie was never quite sure which was the worse nightmare. Why do they have to come in twos and threes in some poor little children’s lives, later she kept asking her Aunt Maggie? One was quite enough, thank you very much. The memory of Mother’s dead white face woke her in a sweat time and again, but the other nightmare was, on balance, much worse. The one where Daddy started coming to her bedroom every Saturday evening, ‘just to say good night, Santie’. Perhaps it was worse because it wasn’t just a nightmare; it actually kept happening every week until finally Santie ran away when she was nearly sixteen. Yes, that nightmare was definitely worse, Santie said to her Aunt Maggie when Santie eventually told her. Being pregnant, Santie really had no option.

It all started about two months after Mommy died. Her daddy came to her bedroom to say goodnight. They had a lovely rough and tumble, which was always quite fun, but then Santie discovered that Daddy’s hands were brushing places where Mommy had often said no boy’s hands should ever venture. Not until she was married, that is.

‘Please don’t do that Daddy. It’s not nice.’ In a culture of early puberty, Santie already had distinct signs of the large breasts that had attracted Klok to Francesca in the first place. She tried pushing his hands away but of course her father was much too strong for his little darling. Arms made strong by shaping, and cutting deep into the virgin wood that he so loved, Santie said bitterly, years later.

‘Please don’t do that Daddy, you’re hurting me. It’s not nice. Please!’ After that there were only sobs. No more words. Until the next Saturday night. ‘Slip into bed, Santie. I’ll be along in a few minutes to say good night.’

‘I’m worried about you Santie. You’ve lost so much weight, and why aren’t you playing tennis anymore?’

‘I’m fine, Auntie Maggie. I just don’t feel like eating much.’ Her kitchen also gave off mouth watering smells, but different to those from her mother’s kitchen. When Santie visited her aunt as a child she would soon be tucking into a piece of melktert, or a plate of oxtail and dumplings.

‘You’ve had a really bad deal in life, Santie.’ Maggie gave her niece a hug, looking down into the sad face that was once so robust and strong. Now it was tense, and an angry blood vessel throbbed on her forehead.

‘Sit down over there and I’m going to make you a nice strong cup of tea.’

‘No, I don’t want to talk about it, Auntie Maggie. I’ll be going home, then.’

‘Santie, I’m going to talk to your headmistress. I want you to see the school psychologist. Is that okay? It’s horrible what happened to your mum. I miss her terribly too, but it is obviously still absolutely ghastly for you.’

‘Please don’t, Auntie. I’m just feeling a little sad. It’s really not because Mommy is dead. Please don’t talk to the teachers.’ Santie pleaded, and her distressed face made Maggie ache.

‘Well then, how about coming to sleep at our house sometimes? Perhaps over the weekend.’

Santie’s face brightened. ‘Oh I’d love to do that Aunt Maggie. Do you think Daddy would let me? Maybe a Saturday night?’

Newsletter

Our newsletter is entitled "create a cyan zone" at your home, preserving both yourself and Mother Earth for future generations; and the family too, of course. We promise not to spam you with daily emails promoting various products. You may get an occasional nudge to buy one of my books.

Here are the back issues.

- Lifestyle and ideal body weight

- What are ultra-processed foods?

- Investing in long-term health

- Diseases from plastic exposure

- Intensive lifestyle management for obesity has limited value

- A world largely devoid of Parkinson's Disease

- The impact of friendly bacteria in the tum on the prevention of cancer

- There's a hole in the bucket

- Everyone is talking about weight loss drugs

- Pull the sweet tooth

- If you suffer from heartburn plant a susu

- Refined maize meal and stunting

- Should agriculture and industry get priority for water and electricity?

- Nature is calling

- Mill your own flour

- Bake your own sourdough bread

- Microplastics from our water

- Alternative types of water storage

- Wear your clothes out

- Comfort foods

- Create a bee-friendly environment

- Go to bed slightly hungry

- Keep bees

- Blue zone folk are religious

- Reduce plastic waste

- Family is important

- What can go in compost?

- Grow broad beans for longevity

- Harvest and store sunshine

- Blue zone exercise

- Harvest and store your rainwater

- Create a cyan zone at your home

It didn’t help of course. Daddy started coming on Friday night to say good night. Sometimes during the week too until eventually the inevitable happened. Daddy couldn’t wait, he just had to say good night to his little darling – but her father had run out of condoms. It was one month before her sixteenth birthday, that Santie realized she had missed her second period. Day after day she agonized. The girl was just skin and bone, and the pulsating artery in her forehead actually started hurting. Instead of cycling to school, she rode around the corner to Aunt Maggie’s house.

‘What is it, darling? Why are you here? You should be in school.’

Santie couldn’t say a word for half an hour, she just sobbed in Maggie’s arms. Then she broke away from her aunt and rushed to the toilet. The retches could be heard all over the house. Finally when she came back, wiping her face, her resolve stiffened, Santie said: ‘I’m pregnant, Aunty Maggie. Two and a bit months, I think.’

Maggie’s face stiffened. ‘How could you do such a thing, you wicked girl? What would your dear mother think? Have you told your father?’

Santie just hung her head.

Maggie gave a deep sigh. ‘Oh, I’m sorry Santie. I shouldn’t have said that. Now I’ve made you cry. So, who is the boy?’

Santie wouldn’t answer.

‘You will have to tell me sometime, Santie. We have to go and talk to him and his parents to see what we’re going to do. Tell me Santie! A name, that’s all I need.’

Santie started sobbing again, deep sobs of agony that welled up from a dark place in her soul. Maggie wanted to be sorry for her, but she was also angry. ‘Why won’t you tell me, Santie? I have to know if I’m going to help you. Please Santie.’ She shook the girl’s shoulder, pleading, followed by a more vigorous, angry shake. ‘You’ve got to tell me, Santie!’

‘It’s Daddy,’ Santie mumbled.

‘Yes, yes, he’s going to be the daddy, but who is he, Santie?’

Santie didn’t say anything for what seemed an interminable few moments but then a deep resolve stiffened her back and strengthened her spirit. ‘It’s not a boy,’ she began, and more tears flowed. ‘It’s not a boy, Auntie. It’s Daddy, I swear.’

Maggie stared at her niece silently, not comprehending.

‘Daddy has come to my bed every week since Mommy died. He is the father of my baby.’ She looked Maggie deep in the eye and, for the first time, held her aunt’s penetrating angry gaze.

Aunt Maggie still couldn’t believe it. She came and kneeled down next to her niece. ‘You mean your father, my brother, has had sex with you and made you pregnant?’ She looked up into her niece’s face, pleading with her to shake her head. ‘Is that what you are trying to tell me? You’re not lying to me, are you?’

Santie nodded, tearing her eyes away from her aunt’s penetrating gaze. Then through deep, wrenching sobs she blurted out: ‘My father…has raped me…every week…since…Mommy died. He is…the father…of …this baby.’ Santie gave a slow shake of her head: ‘I’m not lying to you, Aunty.’ She started weeping again.

When Santie arrived back from the hospital, she found her room in Aunt Maggie’s house brightly made up. The room had been freshly painted and there were new curtains, with a matching duvet cover, and enormous continental pillows just right for sobbing herself to sleep, she thought. All her clothes were neatly packed into the built-in cupboards and there were a few new frocks and blouses, on approval. There was a modern new tennis racquet too with a big head, that she only seen them use on television.

After dinner, when the dishes had been cleared away and neatly stacked in the dishwasher, and the pots washed, Maggie and Santie sat down at the table. Uncle Bob came through with a pot of coffee. ‘You’re going to stay with us now, Santie. This is your home as long as you want to stay here,’ he said. He poured her a large cup of the steaming black liquid and then carefully put it down. He put his arms around her, and was about to say how sorry he was that they hadn’t made it their business to find out what was wrong, but Santie struggled violently, a haunted look on her face. ‘Don’t touch me!’ she shouted.

Bob reared back, astonished. Maggie came around the table between them. ‘Bob, can’t you see the girl’s been hurt. Use your sense, man.’

Later Santie apologized. ‘I’m sorry, Uncle Bob. I don’t know what happened back there. I’m really sorry but I was so afraid when you did that.’

Maggie confided in Bob that night as she lay in her husband’s arms, how she had to get in a female gynaecologist from another town. Santie wouldn’t allow any man near her. Once the air had settled, with Bob seated on the far side of the table, Maggie asked: ‘What do you want to do now, Santie? Go back to school? I think that would be best.’

The girl hesitated: ‘Someone said the police college was very nice, and I think I’d feel safe there.’

Maggie and Bob looked at each other. Bob raised his eyebrow. ‘Now that could just be a very good idea, Santie, but it’s probably too late to get you in for the January intake. A bit of a waste of that brain of yours too, maybe.’ He smiled at her, but Santie wasn’t looking.

Aunt Maggie said: ‘You always came tops until your Mum died. Still, that might be a very good idea. We’ll see what we can do in the morning.’

Santie rapidly regained her strength. She realized there would be a fitness examination, and there would be no mercy. She started eating for three, and jogging or swimming for several hours every day. She even had the odd game of tennis to please her aunt, though it brought her no pleasure. She liked the racquet though. She had plenty of time in the long December holiday and Maggie made sure her brother stayed away.

Surprisingly Santie’s first application was accepted. ‘Look here Aunty, I have to be ready at the central police station in Boksburg at 8 o’clock on the second of January,’ Santie said, reading from a letter that came that afternoon in the post.

Her aunt gave her a hug. ‘This is so exciting for you, Santie. The beginning of something new. Perhaps you can begin to leave behind all the bad stuff that has happened here.’

Santie stared at her, realizing that even her aunt has no real perception of how awful the last five years had been. Not that Maggie didn’t care, that much she knew; not that she didn’t have an imagination, but she obviously did not have any clue as to the depth of the ravages of pain. Nobody did. Or could. It was only years later that Santie eventually realised that no one grasped, not even her Aunt Maggie, that little girls could not even begin to understand how the great powers of the universe might snatch a little girl’s mother away, and allow fathers do something even worse to them. Santie was, to all intents and purposes, an orphan at sixteen. She realized that there was no point trying to tell her aunt that ‘leaving all the bad stuff behind’ was no more feasible than flying to the moon. Instead she took to taking long runs through the forests.

‘My one concern, Santie, is that very able brain of yours,’ said her uncle one evening. ‘How about signing up for a few subjects so you can finish your matric through correspondence college?’

Santie nodded her head. ‘I think that would be a very good idea, Uncle Bob. Do you think I would have time, though?’ She had come to love her Uncle Bob, and even trust him a little.

- Go from Santie Veenstra to Ch 11. Police College

"Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what happens to him."

- Aldous Huxley, novelist

Hyde Park Corner @ Santie Veenstra

It's unthinkable, but it happens on a regular on-going basis that men sexually abuse children, often with the presumed assent and knowledge of the mother, or other female in the house.

Sadly, some priests, prevented from having normal sex, also prey on children.

I am treating two women in the clinic who have confided that they were systematically raped by a father or uncle. And a woman who is having an affair with her priest.

Whatever the situation, if it comes to light that a child is being abused, a report to the authorities is surely mandatory, even if it's your own husband, priest, brother... Surely so.

What happened to Santie Veenstra was no freak phenomenon. It's happening today and probably in a home near you.

What causes headache?

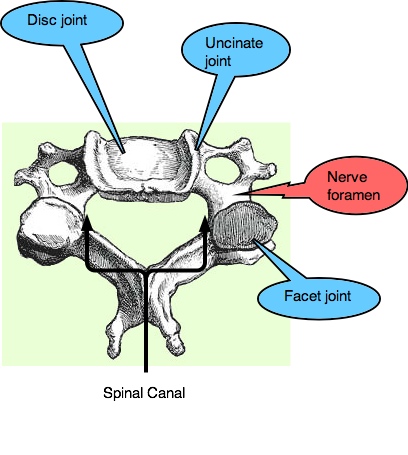

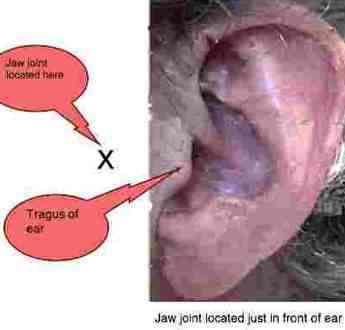

The management of headache is an important and daily task in every Chiropractic Clinic. Whilst 70% of headaches come from a facet joint fixation in the upper neck, every chiropractor, thinking What causes headaches ...? is aware of the rare but always possibly presence of brain tumours and meningitis. The jaw joint is a common cause of migraine headaches; was this the cause of the headaches that Santie Veenstra suffered from?

- WHAT CAUSES HEADACHE ...

- MENINGITIS ...

- MIGRAINE HEADACHE ...

Use the Site Search function in the navigation bar on your left to find the links to those topics highlighted in bold.

Nutritious choice foods

Bernard Preston's website and books are about stepping up to the place where life is better. It's hard work achieving greater wellbeing, no question of it but the alternative is too ghastly to contemplate. Amidst the controversy, it became a focus of Santie Veenstra and Janet's life together.

Nutritious choice foods is an important part of this website. Research shows those who eat eight coloured foods per day have a 33% lower all cause of death; that's massive.

Impossible? Nonsense, I probably enjoy 10 - 15 most days. Start the days with a few prunes, and fresh citrus juice and you already have four.

Add our hummus recipe to your lunch, made in only four minutes, and you have another three at least.

- Quick constipation relief with prunes.

- Citrus fruit list

Five citrus fruits, freshly squeezed, are enjoyed by my family most days. It takes less than five minutes. Already we are half way to achieving our ten coloured foods; don't bother with whether it is a full helping or not, or you'll just end up suffering from a sad wellness nut neurosis.

Did you find this page interesting? How about forwarding it to a friendly book or food junkie? Better still, a social media tick would help.

- Bernard Preston homepage

- A Family Affair

- Santie Veenstra

Address:

56 Groenekloof Rd,

Hilton, KZN

South Africa

Website:

https://www.bernard-preston.com