Klok Veenstra

Klok Veenstra, is chapter seven from a Family Affair by Bernard Preston; meet the other villain of the piece.

This page was last updated by Bernard Preston on 6th May, 2020.

Planning the end is an exhausting affair I can assure you. It’s three months since I came to the realisation that I can no longer live with myself; the memory of what happened thirty years ago has given me gnawing ulcers and made me the loneliest man in the world. I wake every night in a sweat, tossing and turning, unable to escape the guilt, even after all this time; but now finally everything is settled.

Sipho and I shook hands on an amicable arrangement whereby he now has all the tools of my trade in exchange for a settlement terminating his services over the last twenty years. He is the winner; the machines are worth at least twice what I owe him, and the skills I have taught him over that time are priceless.

Neither he, the poor orphan who arrived on my doorstep, aged twelve, nor his growing family, will ever go hungry. I have taught him to fish; that’s one of the few items on the credit side of my life. The house is sold and the proceeds paid off the bond on Safe House. That’s the least I could do to make amends.

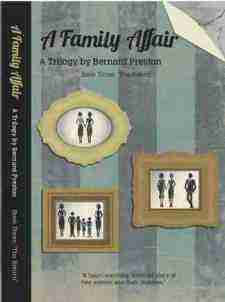

A Family Affair

A Family Affair is a trilogy written by Bernard Preston; Klok Veenstra is a man torn asunder by the sudden death of his wife.

Klok Veenstra

Klok Veenstra invites you to meet the source of Santie's pain; he's Carlo's grandfather.

The last two grandfather clocks are finished. They have taken me nearly a year to complete. One is on its way to Pretoria, where I have engaged the services of a local clockmaker to install it. It has to be that way; Santie wouldn’t accept the gift if she knew who made it. I haven’t seen her in person since that day, so long ago, when I secretly attended the Police College graduating parade. Actually it was the dress rehearsal for the final parade, but more about that later. Santie never made the final parade, though I never discovered why until my grandson, Carlo, explained it all to me years later. What a beautiful young woman Santie was, just like her mother, so smart in her uniform, with her thick black curly hair bursting out from under her beret, as she marched up and down with a burly, swaggering young policeman. A handsome couple I thought but, even from that distance, I could feel the reserve between them as they saluted the stand-in Minister of Defence and all the top brass. The top cadets from that entry I heard someone saying.

Actually I have seen Santie on TV a couple of times over the years, though not recently. She’s quite a big shot, they tell me. I could hardly believe my ears when I heard it for the first time. Surely there must be two Santie Veenstras? There I go again, getting ahead of myself as usual, but that’s the privilege of an old man. My mind does wander, I admit, the events of the last millennium all mingled in with packing up my last few possessions yesterday. The other clock is on its way to Cape Town to the home of a Mrs Ina de Klerk, carefully packed in a crate in the baggage wagon of this very train, and I am comfortably settled on my last journey. I buy the mechanisms for my clocks from a Swiss manufacturer who guarantees them to within three seconds a month. They are good, the best in the world – but then for R75 000 you would expect them to be accurate. If they are correctly set up, I find I can guarantee my clocks to within a few seconds a year. I will do that myself for Mrs Klein and her payment will pay handsomely for this last indulgence.

And so I find myself, a tired, taciturn old man, sitting back comfortably on the Blue Train, waiting to depart from Pretoria station. Promptly at noon says the brochure. We’ll see. This must be one of the most luxurious and expensive trains in the world, I think to myself. I don’t have much to say anymore. Mostly I just think. It’s easier that way. No one is much interested in my ideas anyway and, for reasons that will become obvious to you dear reader, I don’t like to talk about my past. That small leather suitcase up there on that rack above my head contains the only possessions I have left in this world. I won’t miss any of my them, except my dignity, that is. I always did want to die with dignity, but that is one commodity I will certainly be without as I take the last gap. I wonder if it will be any easier than when I had a rugger ball tucked under my arm?

Dignity. It couldn’t be otherwise after what I did and I still don’t really understand why. Well, my wife died. I suppose I could use that to try and justify things, but it won’t wash will it? The very thing that I hated, I went and did. I am so ashamed of myself. A horrible, nasty old man, so don’t go feeling any sympathy for me. I don’t deserve it. I’m not expecting any on the other side either, if there is one. All my life I’ve been counting on that being a lot of old claptrap, ashes to ashes was always my motto but, now that I’m on verge, I’m must confess I’m less sure.

I love trains, always have, right back from the days when the old belching steam train took me home to Waterval Onder at the end of every term. This is my final tribute to my life, my final not-so-small luxury before I finish it all. I can’t quite make up my mind – Table Mountain or an Oleander salad? I think the mountain. Quicker, if not cleaner. Of course the salad would put me in the company of good men like Socrates. He wasn’t given the Table Mountain option, poor chap. I once watched a friend tremble and collapse, rapidly sinking into a coma and dying when he used an Oleander stick to barbecue his warthog chops. It was only years later that I learnt that the local name is Dune Poison-bush and it contains the poison of choice used by the Bushmen for their arrows. There was nothing I could do to save him, stuck as we were on that remote hunting trip in the Lowveld. No, it’s the mountain for me.

It’s very comfortable as I watch the bustle. That boring platform clock is probably even more accurate than my last two masterpieces – except that the electricity is now less reliable than the gravity that drives my clocks. It reads fifteen minutes to twelve. Fifteen minutes until the last journey of my life starts. Well, at least it’s in style. I snap the window closed, the smell of putrid fat, and cheap sausages being barbecued on the station platform is nauseating. Couldn’t we leave a few minutes early? My head nods and I try to settle more comfortably into the luxurious leather. In a flash I am transported back half a century by the arms of Morpheus to a Viscount seat, much less comfortable, winging my way to Italy to join a rugby club in Bologna. I have been appointed their first player/coach. My eyes dart about rapidly under their lids, revisiting those first matches, the triumphs and losses of our team and my tiny apartment in the Fondo Beluzzi, as though it was only yesterday. Oh, and that day that I was swept off my feet by Santie’s mother. How you could dance, Francesca! I watch the replay several times over, as you swirl and twirl, with your soaring skirts and noisy castanets, and your father and brothers squat over their guitars while the people, full of cheap red wine, clap and sing along. Francesca’s family is really Spanish. Their forebears fled in the early 1800s to Italy to escape the Napoleonic invasions. That so-called ‘Peninsular War’ may have destroyed the fabric of Spain, but it is was the making of me. How otherwise would Francesca’s beautiful genes have been carried across the sea to the little village of Cantona. All thanks be to Napoleon, cruel bastard that he was. The only way I managed to break through the ring of steel the Contis built around the Rose of Bologna, as they called Francesca, was to take up a job working all my spare hours in her father’s guitar factory. It was enough. Despite their best efforts, Francesca fell in love with the handsome devil, as I became known.

What a stunning bride Francesca makes, as my rapid eye movements fleetingly follow those delicious days of my life. I wake with a jolt, as the bone in my neck splinters – that tackle on Guiardo Olivetti ended my rugby career in an instant, but I find myself instead, regretfully slumped over in my seat in the Blue Train. Awake again, I gaze out of the coach window. Grey, fetid smoke wafts across the platform, but fortunately my closed window keeps most of the malodorous stench out. There is more bustle as families embrace, and dozens of colourfully dressed tourists eagerly climb aboard, and there are yet more late arrivals. I check the station clock, astonished, it reads twelve minutes to twelve. Only three minutes have passed. Call that a clock? ‘n Klok? Fooitog.

My head droops again, my eyelids too, concealing my eyes as they dart about watching the wife of my dreams setting up home in our tiny, humble apartment in Brakpan, which is all a broken down rugby player can afford. There was no insurance in those days but, fortunately for me, Francesca does all things well. Well, almost all things. She doesn’t bear babies well but I’m getting ahead of myself again. My friends are jealous as hell, and I have to beat a good few of them off. Francesca could have achieved everything Sophia Loren did, but she had the misfortune to meet a South African rugby player with a bulge in his pants that he couldn’t control, and a neck that wasn’t as strong as he thought. At least I didn’t end up in wheelchair though they tell me it was close. Ah, Francesca! A cook as good as any that you could find in Italy, a tigress in my bed, and she boasted one other gift that was to save our bacon. Francesca could hit a tennis ball, not just well, but astonishingly well for such a tiny woman. Today she could have played the international circuit, given the opportunity, but she wasn’t. Her father didn’t believe in daughters going off to strange places, and sleeping in strange hotels with strange men. She was runner-up in the Transvaal Open that first year, but after that I had my way, and Santie started making her presence felt. It was tennis coaching that kept food on our table. Few people had the money to pay for handmade guitars.

I am an ordinary sort of man. Big and fast, with not much between the ears, and that uncontrollable bulge in my pants when a pretty girl walks past. That bulge would ultimately be my downfall, but in those good years Francesca satisfied all my needs in that department. Until she died that is. That’s when my problems started. I finally managed to find a reasonable job selling second-hand cars, but it was the woman in my bed, and my growing love of our child that made life wonderfully satisfying. Little Santie, enough to make any father proud, though her arrival into the world was inauspicious. Bum first, causing all sorts of damage on the way out, so that Francesca had to have a hysterectomy within a year. No more babies, but that didn’t stop Francesca and I trying.

Santie is the spitting image of her beautiful mother. Dark black eyes, and a mass of curls that would never need curling, and the prettiest little dimple. Life was good, even if we didn’t have much money.There was one other thing I could do well, to my surprise. When it was clear that Francesca had taken a shine to the big South African, and there was nothing her father or brothers could do to make her change my mind, I was dragged into the Conti band. I have always sung in the bath - but don’t we all? - and few of us dream that we might actually be any good. My introduction to public singing was in the pub, of course. No one recognised any talent in the Boksburg pubs, but those bawdy rugby songs in Bologna’s pubs brought some fame. Francesca’s brothers soon had me trying simple operettas, but progress only really started after my future father-in-law saw that I really had potential and sent me for lessons with his friend Enrico Canutti. “You are a natural tenor,” Enrico said, “definitely trainable and, while it’s far too late to turn you into a professional, you will be very useful in the Conti band.”

Before the first year was up, I was chosen for the lead part at weddings, and funerals too. The Italians believe in a good send off. The Conti’s first love, though, was singing at festivals, while Francesca danced, and her menfolk played their guitars, and accompanied us as we sang. Our four powerful male voices together with her soprano, and a reasonable repertoire made us moderately famous throughout the region. Then there was that fateful tackle on Guiardo and six weeks in traction changed all our best laid plans.

Shrilly, a bell rings, and my head snaps up. Ten to twelve, only two minutes, but another ten years have flashed before my eyes. There is some shouting and another group of latecomers charge up the stairs and onto the platform. I say a family, but actually it’s two women in their forties and four handsome children.

I shake my head. Surely I am still dreaming; there is a young man, probably seventeen or eighteen, dressed in a Red Devils rugby jersey and he looks astonishingly like me; well, like I did fifty years ago.

I must be crazy. I wipe my rheumy eyes with a dirty handkerchief, staring at him and the rest of his family. I gasp, rubbing my face again frantically. No doubt about it, the big strong woman, expensively dressed in a smart suit with a dark blue check, with a red ribbon in her thick dark hair, is my daughter Santie. Not a trace of grey but then perhaps she gets some help from Elizabeth Arden, I think vaguely to myself.

They are charging across the platform, and I tear my eyes away from her back to the lad. My God, he is my grandson; I know it. Francesca’s genes were more robust than mine in the first generation but, here am I, the late comer.

Francesca always used to say I would be late for my own funeral. She never mentioned anything about being early with hers, though. Her character too was much stronger than my weak uncontrollable nature. I wonder what the boy has inherited in that department? My old eyes go in search of the rest of the family, but they are already past and all I can hear is them shouting and being yelled at, as their bags bring up the rear, and they climb into my carriage. I reach for my old sweat stained leather hat, pulling it firmly down over my old head, and jam my pipe into the corner of my mouth.

Santie has never seen me smoking; I only went back to my pipe after she abruptly left home, but I don’t want to tell you about that. I look hastily into the mirror, and see only a broken old man, with a dirty stained white beard. My nose is still very crooked from the punch I took from Francesca’s brother, but it’s the lips that might give me away. They are full and sensuous but fortunately my weak chin is hidden by tobacco stained fluff. Santie must not recognize her father.

I discover my family has moved into a compartment only three doors away from their sire. We will share the next twenty-four hours on the long trek across the Karoo to Bartholomeu Diaz’s Cape of Storms.

With a jolt, I fall back against the seat and, before I know it, my ancient brain has slipped back into the dream world. Back to those ten years that were the happiest of my life. Everything in my life, could be described in a before and an after. I suppose it would be melodramatic to describe it as a sort of B.C. and A.D. but that one sneeze on Francesca as she was coming home on the bus changed my life as dramatically as the arrival of the Christchild changed the world. No man could have asked for a better wife. Francesca resisted the efforts of my best friend to ensnare her; as a good Catholic she knew well what the Afrikaans word trouw meant, even if she couldn’t speak the language. The same word for marriage and faithful, except there isn’t much faithfulness in marriage these days, I guess. That was one of my virtues. I had no desire, or need, to sleep around. Francesca was of course terribly homesick, until she learnt to speak a little English and Afrikaans, but we did everything together, and that helped. She even assisted me in my little carpentry shop in the garage behind our home, while the old Beetle lived outside. Francesca gave her everything to caring for us. We sang together, of course, and even as a toddler, Santie would cry di piú, di piú! and clap with joy as Francesca danced around the kitchen floor. More, more.

Francesca never went back to serious tennis, but as soon as little Santie could hold a racquet, she had our daughter bashing balls about in the garden. It wasn’t many years before Santie was playing tennis every day for an hour after school, and two hours at the club on Saturdays. She was supple like her mother but with my heavy muscled shoulders, and astonishingly fast around the court. By the time she was ten she could already whip me. How I loved that! It was obvious that our daughter was bound for stardom. Perhaps more important, Santie topped the class averages every year, blessed not only with her mother’s beauty but her brains as well. But all that was B.S. – before sneeze.

I am wakened by a loud clanging of bells and a toot-toot from the locomotive as the train starts to roll smoothly out of the station. It’s quite unlike those sooty steam engines that tugged us up from the Lowveld but, like them, I can feel it loves to draw attention to itself, yet with a certain cocky self-assurance that only the Blue Train can exude. My head snaps back into the erect position and I just have time to catch a glimpse of that nasty clock. One minute past twelve. I scratch my head; what was that strange dream about? The station platform is clearing rapidly as we leave the station, and I am a bewildered old man.I need some air, the summer heat is suffocating, so I go through to the corridor and open the window, staring out at the outskirts of Pretoria. A handsome middle-aged woman in a dark blue check skirt comes out of a compartment, three doors away and heads towards me on her way to the toilet. I give an involuntary tremble. That was no dream! I hold my hat tightly on my head, and gaze steadfastly out of the window. She doesn’t give me a second look as she squeezes past in the narrow corridor. I heave an enormous sigh of relief; I am just an anonymous, ordinary old man.

I choose an early dinner. I don’t sleep well on a full stomach. That’s why, ever since we married, Francesca fed me promptly at six every evening. There was just enough time for a shower after work, scrubbing the sawdust out of my hair, and then a nice cup of tea, before the little dinner gong summoned Santie and me. When you are all alone, with no one to talk to, then you learn to debate with yourself. A bottle of wine will wake me, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, at around three in the morning and that will be the end of sleep for me. With only half a dozen more nights before I take the cable car up the mountain (or should I walk, and savour that last day?) I desperately want a decent night’s sleep. On the other hand, what the hell, I think. When it’s the last week of your life, who needs sleep anyway? The waiter shows me to a table in the far corner of the restaurant car, and I realize that I am facing out into the saloon where everybody can see me. I’ll just have to keep my hat on. I make myself comfortable, still arguing with myself about the wine, and happy that I have the dining car almost to myself. A hint of roasting meat and rosemary and garlic wafts through the swinging kitchen doors, giving a hint of a promised Karoo leg of lamb or mutton cutlets for dinner.

I look around, enjoying the atmosphere. It’s been a long time since I have eaten with real silver cutlery and enjoyed my wine out of crystal goblets. I spit on my finger and rub it gently around the edge of the larger glass bringing out a low, sweet sounding hum. Is that D or C sharp I wonder, wishing I had perfect pitch?

Then I try the smaller white wine glass and I am happier with it and hum a little. One of the guests looks up, smiling at me, and I hurriedly stop. It’s bringing old memories flooding back, though; it’s the first note of one of La Traviata’s great solos that I used to sing so long ago, and I mentally wade through the piece, seeing, in my mind’s eye, the Italian square where Francesca and I used to perform every Saturday.

Night comes slowly in the north, and the terraces are flooded in the long summer evenings with people, young and old, gaily dressed and ready to clap the dancers on, and enjoy the Flamenco music.

Newsletter

Our newsletter is entitled "create a cyan zone" at your home, preserving both yourself and Mother Earth for future generations; and the family too, of course. We promise not to spam you with daily emails promoting various products. You may get an occasional nudge to buy one of my books.

Here are the back issues.

- Lifestyle and ideal body weight

- What are ultra-processed foods?

- Investing in long-term health

- Diseases from plastic exposure

- Intensive lifestyle management for obesity has limited value

- A world largely devoid of Parkinson's Disease

- The impact of friendly bacteria in the tum on the prevention of cancer

- There's a hole in the bucket

- Everyone is talking about weight loss drugs

- Pull the sweet tooth

- If you suffer from heartburn plant a susu

- Refined maize meal and stunting

- Should agriculture and industry get priority for water and electricity?

- Nature is calling

- Mill your own flour

- Bake your own sourdough bread

- Microplastics from our water

- Alternative types of water storage

- Wear your clothes out

- Comfort foods

- Create a bee-friendly environment

- Go to bed slightly hungry

- Keep bees

- Blue zone folk are religious

- Reduce plastic waste

- Family is important

- What can go in compost?

- Grow broad beans for longevity

- Harvest and store sunshine

- Blue zone exercise

- Harvest and store your rainwater

- Create a cyan zone at your home

That only exception was when a match left me with a broken maxilla, or a few torn ligaments. I reflexively rub my cheek and crooked nose, picturing Francesca’s brother who reshaped my face when I had caressed her leg at the bar one night; a good man, I reflect.

I would have done the same, but Maggie, my sister, was never one to flirt, as she did. Oh, my love, how I miss you. Why did it have to happen to us? You who were so breathtaking, so good. A melancholic flood of nostalgia sweeps over me, and I hurriedly disguise my feelings, trying desperately not to acknowledge them by calling the waiter.

I have forgotten some of Verdi’s words and, irritated, I decide that I really don’t give a fig if monkey brain disturbs my sleep after all, even if it is one of my last. Perhaps, especially so, though it’s only in my slumbers that I find solace from my guilt. Oh why, did I ruin our lives? I can’t figure it out, particular because I can’t even get it up now but, back then, the need, the desire was so strong; the very devil.

I choose a Black Label beer instead. The wine steward scowls at me. I can see him thinking to himself, the man has no class. A lager with dinner, huh. I look through the menu whilst the order from the bar is coming and like the look of the Greek salad, described as au naturel and wonder if they use a decent olive oil. That’s one thing that living for five summers in Italy taught me; a taste for good oil. I hadn’t been caught out by the crook who had sold bogus stuff to an unsuspecting, untutored South African public for over a year.

I sip my beer silently, taking a glass of water at the same time, so that I will stay sober, and not let out my dreadful secret. That would be too ghastly. I like the strong beer, weak really compared to some of the beers of Europe, but then I never really liked those sweet beers that the monks seem to favour. I laugh our loud, remembering the first time Francesca and I made love. It was in the park-like grounds of a monastery. We had bought half a dozen Trappist beers and got very drunk, very quickly. It was only the next morning that I looked more carefully at the bottle. 11.6% alcohol. Perhaps they are denied certain pleasures in life, but those monks certainly know how to enjoy a good drink. I sigh contentedly. How we laughed together when we read the label in the early morning. Neither of us had any regrets.

However, it’s my grandson in a Red Devils jersey that is starting to tease my mind as I do some quick calculations. A staggering thought suddenly blows my mind, making me gasp. Could he be my son? No, no, he’s far too young. I take in a deep breath, sighing with relief. I am sad that nobody told me about my grandson. Surely Maggie knew, but then she wouldn’t have said anything anyway. I am about halfway through my first beer and the water glass is empty when Santie, dressed in a simple white cotton dress with a deep red Poinsettia pinned in her hair, and her family arrived. They are six in all, the other woman, and four children, two boys and two girls. With a start, I pull my hat down even further and peer down at the menu again, needlessly as the new arrivals pay no attention to the other guests. Nevertheless I am glad when, on looking up, I note that Santie has her back to me. Facing me, is my grandson. He looks uncomfortable in collar and tie and a very smart checked sports coat. An unexpected frisson, a veritable spurt of pleasure, mixed with sadness, snakes its way up my spine. I will probably never even have the opportunity to speak with the lad, let alone watch him play rugby. I know he plays rugby. I can recognise a kindred spirit anywhere. The sports coat does no justice to the boy’s bulging shoulders, but it is the powerful hands and forearm that impress me. Just like my own. The lad is being teased by a pretty red-headed girl who easily senses the boy’s discomfort at having to dress up for dinner. His sister? No, I shake my head. She isn’t my flesh and blood; there are no redheads in the Veenstra family. I look at the other two children. No, they aren’t mine either.

The main course comes, and I am not surprised to find lamb cutlets, roast potatoes and green peas. Ah! Lovely! I discover thick slices of pumpkin in a turine, roasted with ample butter, well soaked into deep cuts through the flesh. I take a deep sniff, ah, the smell of a shake of cinnamon over the pumpkin wafts up from the large porcelain bowl. The portions are generous. I decide on a bottle of red wine anyway to go with the lamb, and by that stage, it didn’t make any difference whether the salad is dribbled with the thick, extra virgin olive oil from the Karoo, unrefined the way I like it, or a bogus look alike. Sitting next to my grandson, also facing me, is the other woman. Like Santie, she is elegantly but simply dressed, with a trace of grey in her blonde hair, with a chain of red and grey African beads hanging loosely around her neck. I don’t recognize her at all, but I sense that she is the mother of the other three children. Where are the men in their lives? Is Santie divorced? The other woman is tall and quite handsome, though I personally wouldn’t call her beautiful. Silly, but I feel a bit anxious with blondes.

THOUGHT:This is early unedited edition of A Family Affair by Bernard Preston, a story about women in love, is only published to wet your appetite. The fully edited version is now available for only 99c as an ebook to be read on your smartphone, tablet or Kindle.

- To go from KLOK VEENSTRA to Ch8 Blue Train Blue Moon ... the next chapter in our Family Affair saga.

- Return to Summer Holiday Plans; chapter 6.

Hyde Park Corner

Hyde park corner is some place to place my soapbox; where I can sound off between writing stories like Klok Veenstra; give it the miss, perhaps?

Feeling stressed? There's no place like the Garden Cathedral to de-stress. Get your fingers in the earth, plant some radish seeds, you'll be enjoying them in 3-4 weeks or, my favourite, green pole beans.

Life gives us some hard knocks, and out in the garden we can enjoy some stillness and peace. You might even discover that the Good Lord doesn't only abide in cathedrals... in fact, be still and know that I am God is easier to practise in the stillness of the garden than a church...

Choice foods

Healthy choice foods are one of the factors that enabled Klok Veenstra to reach his eightieth orbit of the sun with all his marbles intact; in fact, a life without medication.

Generally we eat from far too narrow a range of foods. Sufferin succotash ( SUCCOTASH RECIPE ) needs a bit of planning and patience but really a couple of rows of corn and lima beans planted this spring will be so rewarding and healthy.

Whenever you plant two rows of ANYTHING always slip a row of radishes between them; they mature in about three to four weeks.

WEll-being

This is just another spot for me to place my soapbox; no less important that old men like Klok Veenstra raping their daughters.

It distresses me that so many folk think, or are told, that painkillers for headaches is the only treatment, and that Chiropractic manipulation of the neck is positively dangerous.

I have been a DC for 40 years now, and not had one serious incident after neck manipulation. Yes, it can happen, to be sure... CHIROPRACTIC IATROGENIC ILLNESS ... aka Doctor-caused disease, but in comparison with taking pills month in and month out, the dangers of kidney and liver damage, it's a very safe procedure; why else are our insurance premiums so low?

- What causes headache?

Type these terms into this Google search engine.

Did you find this page interesting? How about forwarding it to a friendly book or food junkie? Better still, a social media tick would help.

Address:

56 Groenekloof Rd,

Hilton, KZN

South Africa

Website:

https://www.bernard-preston.com