- Bernard Preston homepage

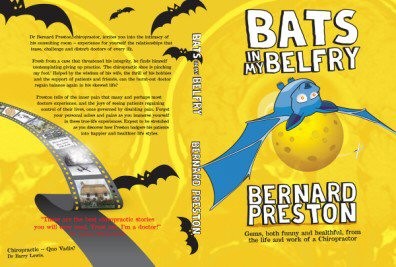

- Bats

- Just Reward

Just Reward

Just reward is a snippet from Bats in my Belfry by Bernard Preston.

Unlike many Black youths, Sipho Khoza had none of the inferiority complex that two generations of Apartheid had inflicted on many South Africans, black and white. His eyes were bright and he looked at me confidently, even insolently. What do you have for me, White man? He had little faith that this strange doctor’s treatment could have a propitious effect on his health, but pain finally drove him in my direction; pain for which medicine had provided no satisfactory answers, though it had undoubtedly saved his life when he was a small boy.

Sipho’s upper back had given him trouble for as long as he could remember: A deep aching pain that sometimes grew to an intolerable crescendo. At sixteen, he was a tall, thin lad, not malnourished, just slender in the Zulu tradition.

His English was good. That too was unusual. An inferior educational system had done its best to ensure that the Black youth remained inferior. Carriers of water and hewers of wood was the curse that Noah, the grand old man of the Bible, had placed on the descendants of his son Ham.

It was no coincidence that Bantu education in South Africa was mostly awful, with only a few pockets of excellence. Apartheid ideologists had carefully crafted it that way, despite smooth assurances of everyone being separate but equal.

This page was last updated by Bernard Preston on 28th December, 2018.

It stemmed actually from the plain bad theology of religious zealots who were under the fanatical conviction that all doctrine could be neatly divided into two kinds; that which was their own and all other that should be neatly bundled together as Communistic, false and dangerous. They were the hands of God, carrying out the curse that He had placed on the descendants of Ham.

Ardent dogmatists would say it confirms the need for the study of doctrine. The curse wasn’t of God; it was that of a drunken old fool, found naked by his son. Ham kindly covered his father with a blanket but, like all fathers, Noah had not appreciated being found out. Education for the races in South Africa was separate and very unequal, and largely remains that way, even twenty plus years post Apartheid.

A Black boy predestined to a life of ignorance and pain. Bad medicine had certainly provided no answers. Actually that is probably unfair; good medicine had saved Sipho’s life from the Tuberculosis bacillus when he was only two. The question, of course, was whether good health care, and now Chiropractic had any better solutions for the debilitating pain that plagued him.

Sipho had one big leg-up in life: a mother who drove herself mercilessly so that she and her son could escape from the ignorance that they were destined to. Deserted by a boyfriend once he discovered that she was pregnant with his child, Miriam Khosa had not been satisfied with the cards that life had dealt her. Having a grandmother in the true African tradition of Ubuntu did help: the old lady cared for baby Sipho while Miriam studied late into the night to become a teacher, whilst working in the day as a domestic help to keep body and soul together. The kindly white madam did help Miriam with her college fees. After graduation it was some years before Mrs Khosa was promoted to headmistress of a small Black community school where she drove her staff with the same flame that burnt in her own soul. After no more than a few short years, theirs was one of the very few schools to get a hundred per cent pass rate in the matriculation exam. Sipho had been privileged to learn excellent English from his mother who insisted on speaking to him only in the universal language of the world. It was she who taught him that faith in oneself is usually the best and safest course. Sipho had unlimited self-belief.

Then tragedy struck. Mrs Khosa was murdered when Sipho was only ten, by a teacher she had fired: he flatly refused to make any attempt to meet the standards she demanded of her staff. Fortunately, knowing that life in South Africa is cheap, Mrs Khosa had the foresight to take out an adequate life insurance policy. Sipho had access to some of the things that White South Africans take for granted. It included Chiropractic care.

The positives of excellent health are additive. So are the negatives of a poor lifestyle: the smoker who is obese; the diabetic who won’t exercise; the workaholic who won’t take proper holidays. They rarely make old bones. Sipho also had many negatives in his young life and they added up to pain; bodily pain and mental anguish for him, but other sorts of pain for those around him.

‘What’s the trouble, Sipho?’ I asked.

‘I have pain in my neck and my back.’

‘When did it start? Do you remember?’

‘As long as I can remember.’

‘Have you been to a doctor? Did they give a diagnosis?’

‘Yes, I have been many times to the hospital. They said I have had tuberculosis. There is nothing they can do, I must just take painkillers.’

‘Do you know when you had TB?’

‘Yes, when I was a baby. I had an operation.’ Sipho took off his shirt, and showed me an ugly scar in the mid back.The poor child, I thought with a shudder. In most of the world TB is a well controlled, almost non-existent disease, but in South Africa, partly because of AIDS, it is rampant. Bone pain from spinal TB is excruciating, and he must have suffered terribly as a child. ‘Sipho was very sick when he was about a year old. His mother took him to the hospital,’ contributed his guardian.

I nodded. Excellent medicine had correctly diagnosed and treated the problem, releasing the abscess with an operation. That was all more than ten years ago, back in the Apartheid era when, ironically, basic medicine was available to the poor for no charge. The medical records that Sipho brought with him from the hospital concluded that there was no active TB.

"Men may not get all they pay for in this world, but they certainly pay for all they get."

- Frederick Douglass

As I went through the active and passive ranges of motion of his neck and upper back, and did the orthopedic and neurological tests that every chiropractor would use, two things were interesting: There was no spinal movement in two distinct areas of Sipho’s spine; one where the tuberculosis bacilli had destroyed and fused the bones of his upper back, and another in the lower neck. The other interesting finding was that orthopedic testing proved that the pain he was experiencing came from neither area: it emanated from the area in between, at the level of the second and third thoracic vertebrae. I had no idea whether I could help him, but clearly new xrays were indicated.

Fortunately for Sipho, the insurance policy that his wise mother had taken out to care for her son, in the event of her premature death, was more than adequate. Perhaps she had a premonition. Not many Black children could afford any form of treatment outside of the rudimentary hospital system, but Sipho’s guardian indicated that there would be no problem. Sipho could go for xrays and payment of my fees would not be a problem.

The x-rays were a shock. Not only was the area in the midback totally distorted by the tuberculous disease but, in the lower neck, Sipho had an unusual condition. Three vertebrae were fused together to form what are called ‘block vertebrae’. It is a fairly rare congenital condition, nothing to do with the TB, but the chances that they occurred simultaneously in the same person were of the same order of magnitude as winning the jackpot. Two areas of Sipho’s spine were fused solid as concrete, one by disease, and the other by a condition that he was born with. Orthopedic and Chiropractic testing indicated that the pain came from the area in between, where there were obviously excessive stresses on his young spine. Two significant negatives that added up to pain.

‘I think I can help you, Sipho,’ I explained to the young man, and his guardian. ‘Just how much I am not sure. Perhaps fifty per cent, maybe more. There will be three phases of the treatment. In the first which will last about four to six weeks, I hope to be able to reduce your pain considerably. In the second, or rehabilitative phase, there will be less treatment from me, but many exercises to strengthen the area. I’m afraid I cannot cure this condition, no one can, so in the third phase you will have a treatment every six to eight weeks in attempt to control the situation. That is the best I have to offer. If it doesn’t work out, then I promise to be honest with you, but you can expect it to be difficult. There will be no miracles; we will both have to work hard.’

‘This TB has nothing to do with AIDS?’ Sipho’s guardian wanted to know.‘I doubt it,’ I replied. ‘He had the infection a long time ago and, if he was infected by the HI virus, then I would have expected to see other signs of AIDS by now.’ Turning to Sipho I asked, ‘You don’t suffer from diarrhoea, or fungal infections?

’He shook his head.‘In all other respects you seem to be a fit, healthy young man, Sipho.’ In theory, I was right but, in practice, quite wrong. ‘Do you have any questions about the treatment plan?’ They shook their heads.

The treatment went according to plan as I treated Sipho’s spine over the following weeks. Another negative in Sipho’s young spine was a 9 mm short right leg, giving him a significant scoliosis, aggravating his neck pain. That was easily dealt with. Fortunately he had the kind of scoliosis that could be remedied by a simple heel lift. Within six weeks Sipho declared that the pain in his back had indeed been reduced by about a half. He was satisfied and so was I, though there were a few surprises along the way.

‘You’ve got some blood on your shirt, Sipho. What happened?’

‘Oh, that’s nothing. I had a little fight.’

‘A fight?’‘We have a very cocky boy in our class. He is always asking for trouble, so I gave it to him.’

‘Let me have a look.’ The ‘little fight’ had given Sipho quite a nasty gash on the chest that was still oozing blood. I bathed it, careful to use gloves, thinking back to my childhood of the styptic stick that my father had used when shaving.‘How did this happen?’

‘He pulled a knife on me. So, of course, I had to use my knife.’I grimaced. ‘Why on earth do you boys take knives to school? This is so dangerous, you could have been killed.

’Sipho grinned. ‘He won’t cheek me again. He’s in hospital!’

The next month it was much the same. Sipho had a broken bone in his hand. ‘What happened, Sipho?’ I asked as I taped up his finger. ‘Oh, it was just a stick fight after school. Nothing much.’

‘But look at your hand. How can you say it is nothing?’‘You should see the other boy!’

‘Don’t tell me. I don’t want to hear. How is your back doing?’

‘It hasn’t been so good this week. I have been getting headaches. Do you think it is coming from my back? I’ve been feeling quite tired lately.’I examined him carefully. The part of his neck that might cause headaches was reasonable. He didn’t have a temperature, and his blood pressure was fine. I gave him an adjustment, wondering if there was something else causing Sipho’s headaches.

The weeks turned into months. Eventually Sipho was faced with his final matriculation exams. ‘How has your back been with all the studying, Sipho? Are you still getting those bad headaches?

’Sipho gave me a broad grin. ‘I’m tired of school, but it’s nearly finished now.’‘And next year? What are your plans?’‘The White lady who teaches me Mathematics thinks I could go to the university. We look after her. Some of the tsotsis have tried three times to steal her car, but we sorted them out.’ He winked.

Sipho fiddled with his cap. I hadn’t noticed it before, but he kept putting it on, and taking it off, and turning it one way or another. ‘Your back? Those headaches?’

‘My back is quite good, but I am very tired. I study late every night. I think that is the cause. The headaches have been bad this week.’

‘I think you should go to the hospital. Get a check up. Your neck is really quite good.’

‘The hospital! You think I am mad? More pills! I don’t ever want to go there again.’ He fiddled with his cap again. It was bright red.

‘That’s a new cap.’ I could hardly have missed it.

‘Yes, it’s a fine cap, isn’t it? I won it in a competition.’

‘Congratulations, Sipho. That’s very nice. Well done. Now that the exams are here, I should see you each week until they are over. There will be lots of extra stress. Then we can go back to a treatment every two months. Now remember the most important rule; read the question carefully in these exams. You can write many pages, but if you don’t answer the question, then you will fail.’ Sipho nodded.

Just Reward

Just reward reveals how Sipho painfully paid in full for what he illicitly stole.

The weeks turned into months. Eventually Sipho was faced with his final matriculation exams. ‘How has your back been with all the studying, Sipho? Are you still getting those bad headaches?’

Sipho gave me a broad grin. "I am tired of school, but it’s nearly finished now."

"And next year? What are your plans?"

‘The White lady who teaches me Mathematics thinks I could go to the university. We look after her. Some of the tsotsis have tried three times to steal her car, but we sorted them out.’ He winked.

Sipho fiddled with his cap. I hadn’t noticed it before, but he kept putting it on, and taking it off, and turning it one way or another. "Your back? Those headaches?"

"My back is quite good, but I am very tired. I study late every night. I think that is the cause. The headaches have been bad this week."

‘I think you should go to the hospital. Get a check up. Your neck is really quite good.’

‘The hospital. You think I am mad? More pills? I don’t ever want to go there again.’ He fiddled with his cap again. It was bright red.

"That’s a new cap." I could hardly have missed it.

"Yes, it’s a fine cap, isn’t it? I won it in a competition."

‘Congratulations, Sipho. That’s very nice. Well done. Now that the exams are here, I should see you each week until they are over. There will be lots of extra stress. Then we can go back to a treatment every two months. Now remember the most important rule; read the question carefully in each test. You can write many pages, but if you don’t answer the question, then you will fail.'

Sipho nodded.

I don’t make much time for the newspaper. Five minutes for the headlines, even less for the sports page, and then a quick scan through the snippets. The first was from Switzerland; orthopedic surgeons expected 25,000 broken legs during the ski season. Many specialists work for five months, and then take off the rest of the year. I sighed; what a life.

The second snippet had me shaking my head in disbelief; the boys in the matric class at Amakolwe High School had organized a new and unique competition; at the beginning of the year they had bought a bright red cap. The first boy to sleep with each girl in his class would win it. Class leaders declined to say who had won the trophy.

Subluxations in the spine have been directly connected with immobilisation arthritis. When full-blown in the low back it may be lead

to a devastating situation. Often it is the anything but just reward for a fall in childhood.

Sipho did not mention it but I knew for a fact that most children have access to only highly refined maize-meal; corn on the cob is a luxury for most.

As part of my nutritional counselling in Just Reward I encouraged him to learn how to grow corn.

Newsletter

Our newsletter is entitled "create a cyan zone" at your home, preserving both yourself and Mother Earth for future generations; and the family too, of course. We promise not to spam you with daily emails promoting various products. You may get an occasional nudge to buy one of my books.

Here are the back issues.

- Lifestyle and ideal body weight

- What are ultra-processed foods?

- Investing in long-term health

- Diseases from plastic exposure

- Intensive lifestyle management for obesity has limited value

- A world largely devoid of Parkinson's Disease

- The impact of friendly bacteria in the tum on the prevention of cancer

- There's a hole in the bucket

- Everyone is talking about weight loss drugs

- Pull the sweet tooth

- If you suffer from heartburn plant a susu

- Refined maize meal and stunting

- Should agriculture and industry get priority for water and electricity?

- Nature is calling

- Mill your own flour

- Bake your own sourdough bread

- Microplastics from our water

- Alternative types of water storage

- Wear your clothes out

- Comfort foods

- Create a bee-friendly environment

- Go to bed slightly hungry

- Keep bees

- Blue zone folk are religious

- Reduce plastic waste

- Family is important

- What can go in compost?

- Grow broad beans for longevity

- Harvest and store sunshine

- Blue zone exercise

- Harvest and store your rainwater

- Create a cyan zone at your home

One of the messages that I did say to Sipho, not mentioned in Just Reward, was about the importance of certain amino acids found in protein. Malnutrition is common in South Africa, and over a quarter of children are permanently stunted[1].

Sesame paste is rich in the amino acid methionine that vegetarians and many of the poorer section of society have difficulty getting, as well as essential fatty acids; and it tastes just fine!

I recommended to him that he enjoy it on bread instead of jam, have it on salad, or use it to make our authentic hummus recipe.

There has been no just reward for attempts to roast and grind sesame seeds to make tahini; the Turks and Greeks have been making it for thousands of years, and it is just better than anything we have succeeded in producing; cheaper too.

Did you find this page interesting? How about forwarding it to a friendly book or food junkie? Better still, a social media tick would help.

- Bernard Preston homepage

- Bats

- Just Reward

Address:

56 Groenekloof Rd,

Hilton, KZN

South Africa

Website:

https://www.bernard-preston.com