- Bernard Preston homepage

- Stones

- Heb Je Geen Zin in Sex

Heb je geen zin in sex?

Heb je geen zin in sex is not a lurid story! Nor is it in Dutch. But why would the words "Have you no pleasure in sex?" find their way into a chiropractic questionaire that every new patient must fill in?

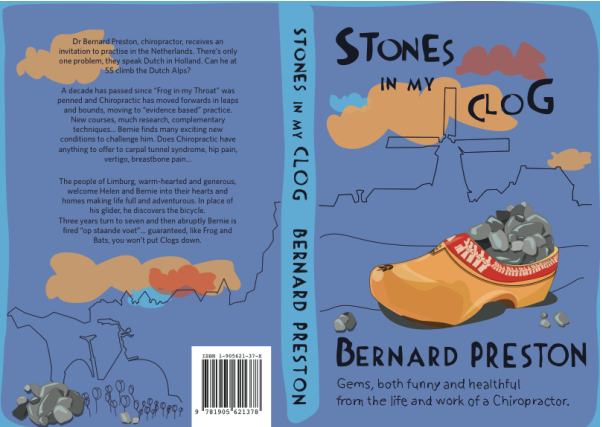

The chapter is lifted as a freebie from Stones in my Clog by Bernard Preston; the book of chiropractic short stories is available from Amazon for about $3.

This page was last updated by Bernard Preston on 9th April, 2023.

"The majority of husbands remind me

of an orangutang trying to play the violin."

Honore de Balzac

Heb je geen zin in sex

But the question in the clinic questionnaire, to be filled out by every new patient, caught me completely by surprise. “Heb je geen zin in sex?” Do you have no desire for sex? I scratched my head when I came across the question that first day in the clinic, not having the language skills or the courage to ask about the question. Why on earth was there a question about sexual appetite in a chiropractic health questionnaire?

Holland is, of course, one of the most sexually liberated countries in the world. Getting quite lost on our first visit to Amsterdam neither Helen nor I realised we were straying into its notorious Red light district, until we spied one of the ‘girls’ sitting quite naked in a bay window beckoning passers-by to partake of her wares. Gay parades attract millions of visitors.

Even in conservative Limburg, most couples have lived together for some years before marriage and many never marry in a legal sense. I would be surprised if one in a hundred brides is a virgin. Helen and I spent many long winter evenings trying to come to terms with this completely new understanding of relationships, of sex, and what it means to be married in twenty-first century Holland. Our conservative minds boggled.

Two things continued to surprise: the number of teenagers who openly stated in the questionnaire that they couldn’t get enough sex, and the number of people, even in their thirties and forties who checked the “Heb je geen zin in sex?” box with a tick.

Being the perverse person I am, interested in the great paradoxes, I started to take more notice of my patient’s replies. Why was the question there anyway? Finally I took the plunge.

‘Good morning, Mrs Barske,’ I said to the tired looking young woman sitting in reception. ‘Will you come this way please?’ I continued, shaking her hand whilst noting the drooping shoulders and the slight look of neglect about her as she walked to my consulting room. Her hair was untidy and the inevitable blonde dye revealed several months of mousy brown hair at its roots. ‘Would you give me a few moments to read through your questionnaire, please?’ She gave a brief smile, and nod of the head, obviously amused at my accent and bad grammar but too polite to say anything. ‘Mm, intermittent pain in the neck and shoulders, headaches two or three times a week, no referral down the arms, no trauma.

Ah, you had to stop taking medicine, because of pain in the stomach. When did this condition begin?’ I went through all the usual questions. Was the condition getting worse, what other treatment had she had, were there any red flags? Mentally I placed the ticks in the favourable outcomes column.

√ Intermittent neck pain

√ Not on sick-leave

√ Not receiving workers’ compensation

x No higher level of education alas

x Obvious fatigue

? Could I convince her of a higher expectation of a beneficial result?

√ No morning pain

√ Good general health

xxx The most important variable however was not good. Pain for three years.

It was some weeks into the treatment before I ventured into the tantalizing new territory. ‘I see you checked the “no interest in sex” box at your first consultation. Do you want to talk about it? You’re not obliged to,’ I added hastily. She was lying face down, out of eye contact, whilst I did some painful cross-friction on her Rhomboid muscles before adjusting her spine. It was some moments before she replied. ‘It’s boring, and I’m too tired anyway at the end of a long day.’

‘Two small children and a full time job must keep you busy,’ I replied.

‘Too busy, yes’ she replied, ‘and don’t forget my other job. Keeping the house, doing the ironing, getting meals together.

‘What does your partner think about it?’ I ventured. They weren’t married. I wondered briefly whose name the children took, making a mental note to ask our secretary what the custom was, careful not to tread on any toes. ‘Oh, fortunately he is also too tired much of the time. He gets angry with me now and again if I refuse, but it’s all over in five minutes.’ ‘How was your sex life early in your relationship?’

‘Oh, pretty good. Not as good as with my last boyfriend until he dumped me, but much better than the first two.’ I absorbed that, Elvis’s words flashing through my mind: You’re so square … ‘So, when did your desire for sex come to an end?’ ‘Oh, don’t get me wrong. I still want to be hugged, and make love occasionally. Perhaps once in a month or two,’ she said defensively. ‘Probably when I went back to work.’ By that time I had finished pummelling her, adjusted her spine and elbow and given her a new exercise. She gave me a dour look on leaving. Had I had opened a raw wound?

I gave the subject some thought over the next few weeks. It had been something of a wound in my own life that our discussion had opened, paralleling my own sex life over the last twenty years. Finally the penny dropped: amongst other things, one’s sex life gives a fairly accurate indicator of over-busyness, exhaustion and the stress of life and it correlates quite well with the knots and pain in patients’ necks and shoulders. I saw one of the great contradictions of life unfolding in Mrs Barske’s life: Fully alive, less than half way through her life, yet the kernel of life being tragically stifled by the daily grind.

So I asked Helen one evening, daring to ask a question that I wouldn’t have broached a year ago. ‘When did our zin in sex end?’ She looked at me with a wry smile. ‘When I went back to teaching after Samantha was born. I would have thought you remembered.’ I nodded. ‘And why do you think it is has been so much better since we came to Holland?’ ‘Oh, you are such a plod!’ she exclaimed. ‘Surely you can work that out.’

Much as I prodded and questioned, Helen wouldn’t give me an answer. No doubt she thought the plod should do some thinking for himself. Freed from many of the responsibilities of life, Holland has done that for us, giving us space and time. Less can be more. It was some weeks before I realized the paradox of how miserable a person can be, surrounded by dozens of other overly busy people. Lonely people looking like houses where nobody lives, the Hump used to sing. Had Helen too been miserably lonely with a husband so immersed in hobbies, work and church?

Mrs Roomans is just a little older than me, a dumpy little woman with a friendly smile. Actually, there are no old women in Holland. Well, no grey-headed ones anyway. She had quite short, stiff blonde hair that stood straight up in the air, thick with gel. They call it ‘moderne’, but I think her hairdresser had a secret crush on Bart Simpson. I hated touching her hair whilst palpating her neck. It was coarse and sticky and perfectly ghastly.

‘When did the pain in the buttock begin, Mrs Roomans?’ ‘About nine months ago.’ ‘Do you know what caused it?’ ‘I think it started a few weeks after I verhuisde .’ I had learnt that word whilst still in the foothills of the Dutch Alps. In the absence of any strong Zulu men, many people move house themselves. I’ve now come to the conclusion that a removal company is a lot cheaper than paying the chiropractor and the neurosurgeon. Less painful too. ‘My husband died very suddenly about a year ago,’ she continued guardedly, ‘so I decided it was time for something smaller. Now I can’t sleep lying on that hip. It’s so painful.’

It didn’t take long to find that most of her pain wasn’t actually in the buttock but mainly on the side of the hip. There’s a small sac of slime called a bursa that protects the hard, bony part of the hip from the muscles of the thigh. Should it become inflamed, sleeping on that side becomes very painful. A quick examination revealed the usual findings: a very active trigger point in a large buttock muscle called the Piriformis and a fixated joint in her lower back. Mostly it’s bread and butter stuff for a chiropractor though very occasionally it can be a sod. I spelt it out for Mrs Roomans, explaining what was causing her pain and how I was going to fix it.

Home treatment too was essential so I emphasised how she should ice the bursa and do some exercises and stretches every day. We were two or three weeks into the treatment when I thought it might be a good time to raise the subject of her husband’s early death. Had she had the opportunity to work through the pain? Or, had no one been willing to talk about it? It’s too awkward. The pain in Mrs Rooman’s hip had by then diminished by about fifty percent and we had gained confidence talking about this and that; sharing her story again – if she had ever shared it properly – might be therapeutic.

‘You said your husband died very suddenly.’ I left the statement open ended. She could talk if she wanted to. ‘Yes, he had a heart attack. Very sudden. It was awful.’ ‘I’m sorry. How old was he?’ ‘Sixty-one.’ ‘That’s miserable. Ten years before his time.’ She nodded. ‘It was my fault really. I had allowed him to get quite overweight which the doctor said was the cause of his diabetes.’ “Bourgondisch” dining is the delightful word the Dutch use. Sumptuous and deadly. ‘You can only live life forwards,’ I said. ‘The past is set fast in concrete, so there’s no point heaping a lot of guilt on yourself.’

‘Yes, but if only I had given him a lot more salads and fruit like the dietician said …’ She was having difficulty going on. ‘Of course all the beer he drank didn’t help either.’ ‘Were you with him when he died?’ It was more than idle curiosity. Telling her story would be healing. She didn’t answer. Finally she said: ‘I’ll tell you next time.’

I had forgotten all about our conversation and was focused on the decision whether I should be fine-tuning the treatment by changing from adjusting Mrs Roomans’s hip-bone to her sacral-bone. The improvement had plateau’s out at sixty percent better and I was concerned that there might be a better way to adjust her pelvis, when she said unexpectedly: ‘You asked me last week if I was with my husband when he died so suddenly.’ She half turned from where she was lying prone on the table so we could talk face to face. ‘We were making love. It was just as we were both climaxing.’ With that she put head down again on the table, weeping quietly.

What does one say? Finally, I gave her shoulder a squeeze and said: ‘Thank you for telling me,’ and went on with my work. ‘Sounds awful, doesn’t it but, compared to my brother-in-law’s lung cancer, it was quick and clean,’ she said eventually. ‘I’ve thought a lot about the way he died, and I have decided there could be no more fitting way. After all the last ten years of our marriage were the best, after the children had left home, and I quit my job.’

‘I suppose you had more quality time together.’ She nodded. ‘And I wasn’t so ratty. Our love life really came alive in those ten years. You know something interesting we discovered: Sex takes five minutes, but to make love took us over an hour, sometimes even two with cups of coffee and a peanut-butter sandwich in between.’ I digested that, and said finally, ‘You’re in good company at least.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Having a heart attack in the middle of orgasm is not that uncommon. I read that the American billionaire Rockefeller died the same way, just with his mistress.’ ‘You call that good company?’

‘Well, no, sorry. Comparisons are odious, and particularly in that instance. Apologies.’ ‘I don’t worship those mammoths of the landscape. Just because he was one of the richest men on the planet. At the end, we’re all equal, aren’t we?’

‘Certainly couldn’t take it with him,’ I said. ‘No, he couldn’t. What was also good about our sex life is that we learnt for the first time how to climax together.’ ‘You mean the sum is more than the individual parts?’

‘Exactly! I regret it couldn’t have gone on longer, but in the end we had a wonderful marriage despite the really tough bits in the middle.’ She brightened up and, after dressing, said to me on her way out: ‘You know that nasty old-wives tale about the acorns in the cookie-jar?’ I shook my head. ‘The story goes that if, every time you have sex in the first year of marriage you put an acorn in a jar, and after the first year, take an acorn out every time you make love, then you will never empty the jar.’ I roared with laughter. With a serious face she said: ‘We emptied and refilled that jar dozens of times! It wasn’t all bad.’ She winked and left.

Meantime, Mrs Barske’s neck was being stubborn. The last twenty percent just wouldn’t go away. Then she had a setback, and the pain started all over again. ‘I want to stop the treatment,’ she said. ‘Why?’ I asked. ‘It’s been so much better!’ ‘No, it’s not improving. I’m no better today that I was two months ago.’ ‘Really?’ I said. ‘Remember the headaches you were having? But, yes, I can see that you are in a lot of pain, this morning. What happened?’ She shrugged her head. ‘I don’t know. Why isn’t it getting properly better?’

‘I’m afraid all the research indicates that if you have neck pain for more than three to six months, that it will probably never go away completely.’ ‘Then why wasn’t it treated properly in the beginning?’ I shrugged my shoulders. ‘When did you first consult your doctor?’ She screwed up her eyes, thinking. The previous week, it had struck that she could really be quite pretty, but the worry lines that crease her forehead were back. I could see she was exhausted. ‘Not for a month or two, I suppose.’

‘And then?’

‘He gave me some pills, and told me to come back in six weeks.’ ‘And then?’ ‘Well, they didn’t do much, so I had another course of stronger medicine. Then after about six months, I suppose, he sent me to a Mensendieck therapist.’ ‘That’s it,’ I said. ‘By the time it’s allowed to become chronic, the chances of getting completely better begin to diminish quite rapidly. I don’t believe a person should rush off to the doctor, or chiropractor, whenever you have a pain, but when it’s obvious that it is not going to get better by itself, I like to treat necks quite aggressively, to prevent this sort of chronicity.’

"But it is too late now, isn’t it? I’ve been back to my doctor and he says more than four manipulations is dangerous, and he’s given me more anti-inflammatories. I am sorry, I could have phoned and just cancelled my next appointment, but I wanted to tell you myself why I am stopping."

I like the Dutch. They can be very direct, and confrontational, but it’s more honest. ‘It’s your decision, Mrs Barske. Thank you for coming in to tell me. I appreciate it. If I may, I’ll phone you in about two months, and find out how you are doing. Okay?’ She nodded. ‘And, if I may say so. If that ulcer starts brewing again, tell your doctor immediately. There’ll be no charge for today.’ She stood abruptly, jutting out her hand, and without another word left. I was surprised later to find that she had insisted on paying for the consultation.

Mrs Roomans wanted to get properly better so she took me seriously about the three phases of chiropractic care. Fortunately her husband had been well insured, so his premature death left her relatively well off. Once the acute pain was over she took to the rehabilitation phase with enthusiasm and then came every two or three months under control as the Dutch say. Mostly I find that, by the time a few months have passed, patients are beginning to stiffen up again, or a new condition had started.

Pain in the shoulder, or a sprained ankle, or something, so I emphasise under control. Still I was surprised when our secretary asked me to phone Mrs Roomans’s doctor. "Good afternoon, doctor, with chiropractor Bernie Preston," I said, using the strange grammar. By then fortunately my Dutch had progressed to the extent that I could converse with most people provided they did not speak too fast or in the Limburg dialect.

‘Ah, thank you for calling. I wanted to find out why after five months of treatment you are still insisting that Mrs Roomans come back for treatment. I have instructed her to stop.’ ‘Mostly, doctor, because she has had that pain in her buttock for nearly a year whilst under your care. I think a fall back is inevitable with such a chronic condition, should she stop care.’ I was not going to give way to his authoritarian approach, but I did appreciate that he had taken the trouble to phone. Not many doctors would have made the effort to confront me like that. It’s healthy.

‘You are making her psychologically dependent on you. I have advised her against continuing the treatment.’ ‘You have a point there. The alternative is an almost certain return of the pain.’

"You krakers are just in this for the money. You are just squeezing more money out of her by making her dependent on you." A crescendo of anger burst from the phone. I was getting angry too. Fortunately I had taken the trouble to peruse her file before phoning.

‘Are you aware doctor that Mrs Roomans had been in pain for nine months when she first consulted me, so much so that she couldn’t sleep properly. You were not averse to prescribing sleeping tablets for her. Was that not making her dependent on your treatment?’

‘Hmmf,’ he hesitated for a moment. I took the opportunity to climb in quickly. ‘Do you remember her husband? He was diabetic I believe. Did you not bring him back regularly under control to monitor his blood glucose? We do exactly the same. It’s called prevention.’

‘That’s different.’

I butted in. "I’m sorry doctor but I have a very busy afternoon starting. Could we meet for over lunch to discuss this further." He hung up.

The Limburgers are a spirited people. Claudia Roomans knew she was benefiting from the occasional but regular treatment and ignored her doctor. Her next consultation was about six weeks later. I was preparing to discuss my conversation with her doctor but she didn’t give me a chance. Once she was lying on her buik (the Dutch laugh if I ask them to lie on their stomachs; it would be like asking someone to lie on their liver) she said: ‘I have never told anybody this but there is one more thing I would like to tell you about my husband. I very nearly lost him when we were in our forties.’

‘Lost him?’

‘Yes, lost him.’

‘You mean he nearly died?’

‘No, that’s not what I mean.’ She hesitated. ‘Like most women, if I didn’t get my way, I would sometimes use the sex weapon. Quite regularly for six or eight weeks I would refuse to have sex with him.’

‘But you had been married for thirty years!’ I exclaimed. ‘True, but were continually at odds.’ I nodded. ‘You have many sayings in Dutch, and we have ours in English too. We would say, you were facing up to each other armed with broken swords.’ She paused, thinking. ‘Broken swords. Mm.’ Continuing, she said: ‘Then a very dear friend of mine came to stay for a week while she was attending a puppets conference here in Limburg.’ ‘Mm,’ I grunted, knowing where this was going. ‘The morning she left she told me that she had come very close to having sex with him while I was out at a bridge tournament. She didn’t, so they said anyway, but she had been the one who had to put on the brake, and she admitted that she only resisted him because I was such a good friend. Many women found him a very attractive man.’ ‘Whew, and you had such good years after that. How did you reconcile it?’

‘I was very angry with him, of course. With her too.’

"I’ll bet. It’s very sad how often people have affairs with their partner’s so-called best friend." Mrs Roomans nodded. ‘Then, before she left my friend asked me a very disturbing question. “When did you last sleep with him, Claudia?” she asked. The telephone gave me a buzz. It meant the waiting room was filling up. The secretary was getting impatient. ‘Thank you for telling me, Mrs Roomans. The last exciting episode will have to wait until our next consultation.’

‘So, did you forgive him?’ I asked at her next visit. ‘Not for a while, but it did get me thinking. The last thing my friend said to me was that she had nearly lost her husband the same way, until she realized that a man who hasn’t had sex for weeks is very vulnerable. She was just trying to warn me.

A few weeks later on the phone she said to me: “Darling, you use the sex weapon and you will lose him. Do you understand that, don’t you? You see they are such vulnerable creatures when they haven’t had their sex. The first floozie who comes along offering him whoopee, and bingo, right before your eyes, he has gone. A clever girl like you can find 101 better methods to get your way.”

‘A good friend.’ I said. ‘Yes, and an honest one. It must have been hard for her, but it saved my marriage. I thought about it a lot in the next few months. I realized that, in the end, that she was right. We women who use sex as a weapon stand a good chance of losing our husbands.’ ‘And men who use sex as a weapon?’ ‘I don’t think there is such a thing,’ she said with a laugh, ‘but men who enjoy their orgasms without bringing their wives to a climax run the same risk.’

I thought about that for a few moments. ‘Sex is a form of communication, I suppose. Refusing to sleep with your partner is like to refusing to talk to them. Then if some other friendly person comes along.’

"Exactly."

Helen and I discuss many of the interesting and titillating stories that came out of my practice. Never before had I heard of a man having a heart attack during sex but it did in fact make sense. Sex is good exercise for the heart and the back – provided all other things were equal, which they weren’t unfortunately in Mr Roomans’s life. ‘They made some great discoveries,’ said Helen, ‘but unfortunately it came to an end prematurely.’ ‘It took some patience though,’ I replied.

Helen nodded. ‘I nearly left you a couple of times, when you went off gliding or getting bees out of someone’s roof.’ ‘You never told me!’ ‘For better or for worse!’ I blushed. ‘Remember that old cliché, We should live and learn but by the time we've learned, it's too late to live.’ ‘We have much to be thankful for. No more butter for you! I don’t want to be a lonely old widow!

When I first arrived in the Netherlands, I was determined not to live in the city, so we chose a tiny ‘op zolder’ apartment on an old farm in a small village about ten kilometres out of town. Our bedroom was right under the eaves, the raindrops drumming on the roof just above the ancient old double bed. We were never far from the elements. For a few short humid weeks in midsummer it would be stiflingly humid under the baking hot tiles and in autumn the furious gales would rattle and whistle the night through.

‘I wonder how many children have been conceived in this bed?’ I asked Helen early one winter morning. A rowdy cockerel, calling for his harem just outside our window, had wakened us in the grey dawn. Matching old, grey photos hung crookedly in one corner of the bedroom reminding me of the forgotten generations of the Jacobs family who had farmed there for over two hundred years. Ours had been the main bedroom, nestled above the barn that was now our lounge, before new house was built. ‘Plenty, I should think,’ she said snuggling up to me. ‘You’re not allowed a harem, but there is one old hen very interested in your charms!’ ‘You want to stuff another acorn into the cookie-jar?’ We had emptied the jar for the first time in the first frenetic weeks in Holland and it was already half full again.

I made one other interesting discovery in that old bed. Thirty years of making love in a modern bed had seriously deprived me. Having a good solid foot-board to push against at the appropriate moment, increases a man’s pleasure by at least fifty percent.

STONES IN MY CLOG has been published as an ebook. The plan is to keep it cheap, $2.99. Read it on your cellphone or Kindle.

Heb je geen zin in sex?

Heb je geen zin in sex is a spicy-story from Preston's next book.